Blog 3: A Short History of Saturation

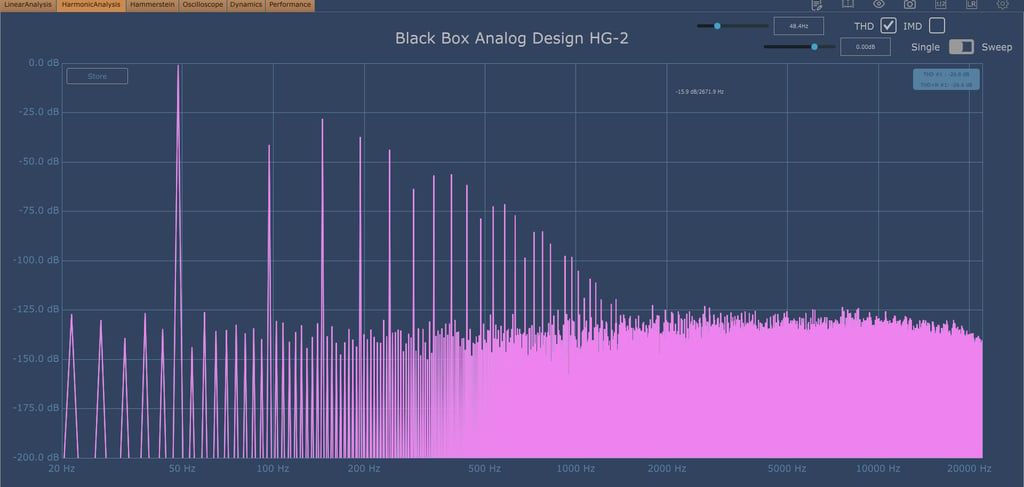

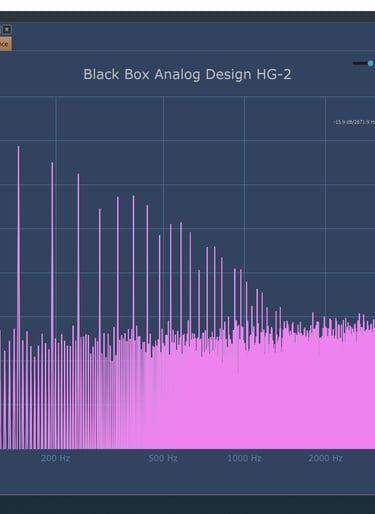

The above image is an Harmonic Analyzer. It shows a basic feature of audio, harmonics. Note that frequencies on the chart are shown on the x axis running horizontally at the bottom. The frequency of the note being played is the tall, spikey frequency at 48 Hz on the far left of the chart, and the harmonics created by that frequency loud enough to be heard are all the tall spikes to its right. (The thick waves running across the graph at the bottom are "noise floor" waves which can't generally be heard as they are at very low decibel levels as shown on the y axis on the far left).

Note the mathematical relationships of the harmonic frequency tall spikes: They double every octave. 48 Hz is the pitch of the note being played, and harmonics are being created at 96 Hz, 192 Hz, 384 Hz, etc. These are called even order harmonics. They generally make the overall sound of the recording “sweet” or “pleasing”. Note also other harmonics are added in between the even order harmonics. Like all recordings, the unique pattern of harmonics gives the sound its unique identifiable characteristics. In this way practically every human voice is distinguishable from every other. In less than a few seconds, one can tell if a voice is that of Frank Sinatra, Paul McCartney, or Eminem even if the three are singing each note of a song in the exact same pitches. The difference in the sound among their voices is these harmonics emanating from the original tone.

Since we explored compression in our last blog, I thought we’d take a look at compression’s first cousin, saturation, in this one. Both of them weirdly share a common feature: a kind of love affair with the past. Let me explain.

In my last blog, I showed how compression is overused. While it is a marvelous tool to “glue” a recording together, it is oft employed to address many additional problems in audio that other more recently-developed technologies can resolve with less problems than the use of compression creates (See blog 2). I explained in that blog how compression’s role in the world of 20th century analog hardware as the "Swiss army knife" of so many audio problems gave rise to a reluctance of some old school engineers to use—or simply to learn about-- digital technologies that are now available.

Saturation, another important tool in the audio engineer’s toolbox, has much the same history. In the 1960’s, electronic amplification of music became commonplace, and as we have discussed in the previous blog, so did the use of analog equipment like consoles, tape machines, compressors, and equalizers. The electric guitar had much of its rise to fame during this period (think of the "British invasion" with the likes of the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Led Zeppelin). Music took on a whole new “vibe”. True, even the time from 1930’s through the 1950’s had its own identifiable "vibes" from the saturation created by the condensers, ribbon microphones and more primitive tape machines, but these were nothing compared to the unique sounds the hardware in the recording studio gave to the music in the 1960's and beyond.

The 1980s brought in the "digital revolution". Now studio recordings were being made on computer generated media instead of through machines that took up a bunch of space. CDs replaced the turntables that had spun the vinyl records, and, it seemed, digital sound spelled a miraculous new era in music. But musician and listening audiences alike soon realized something was missing in the sound: Where did "the vibe" go? It turns out all that studio equipment replaced by the digital world was actually making a major part of the sound that made the music of the 60s and 70s what it was. CDs themselves, many audiophiles complained, were making recorded music sounded sterile and dry. Something was missing.

The physics is not hard to understand. An electric guitar is plugged into an amp and streams electrons into it. The amp increases the volume of the sound and moves the electrons into an EQ and a compressor, each of which adds some additional desired effect and moves the electrons still further down the signal chain. That chain arrives at a tape recorder that which records the guitar performance. But something else was happening during this process: As the electricity moved through the amp, the amp itself started to shake a little. The vibrations of the amp itself added its own sound. It wrapped the guitar signal into those vibrations and sent the altered signal to the other equipment down the line. Each piece of equipment, including the tape machine, in turn, would "shake" or vibrate subtly, adding to the recording its own "contribution".

This phenomenon is called harmonic distortion. Moreover, if the guitarist cranked her guitar beyond the capacity of the electrons in the amp to all flow smoothly through it, it would cause the amp to shake the sound of the notes even further. This is called overdrive. That result, it was discovered, was often something pretty cool. If she cranked it even more, the electrons can't all get through at once, and this phenomenon is called feedback, which could either be a good thing or a bad thing depending on the effect the musician was trying to create.

The result of these developments was that audio engineers in the new "digital age" began to seek out replicating the unique sounds that were created by this earlier analog equipment. The unique vibe of a Pultec EQ, a Neve compressor, an Abbey Road Redd console, or a Studer A 80 tape machine became sought after possessions. But while some music studio owners went on hunts for these vintage—and now very expensive--machines, software engineers began replicating these unique sounds digitally.

Their replication attempts have been remarkably successful. Now many Emmy winning audio engineers such as Andrew Scheps (Adele, Red Hot Chili Peppers) boast mixing almost exclusively in digital technology. Indeed, the days of recording studios with stacks of analog machinery have been replaced with home recording studios that have the ability to mix awesome "vibes" into music in an acoustically treated room containing a computer and some ancillary hardware. The "thousands of dollars" of equipment is now inside the computer in the form of software programs.

With that whirlwind review of the history of harmonics in recorded music behind us, let me share a few of my personal experiences with using saturation as an audio engineer.

I can remember back now almost a decade ago when I didn’t own a single plugin (those software programs I just referenced). My audio mixing career started first as a desire to use my own spoken voice to do voiceovers and book narrations. I soon realized I needed some special equipment to do this beyond just a mic and my computer, namely a digital audio interface (DAI) and digital audio workstation (DAW).

When I learned that the recordings of my voice that I made needed something called "plugins", software programs to bring the sound of the recording to professional standards, I was off on another purchasing binge.

But which ones to buy? Many of these mixing gurus offering fee-paid courses on post production training said I should get “emulation plugins”. An emulation plugin is a saturation plugin that seeks to emulate the sound of one of these old pieces of audio equipment. They are thus advertised as a kind of “two for one”—you get, say, a compressor, but you also get a way to saturate the mix or other recording that you play through it.

One day I heard once such emulation plugin being touted on an online post production video. It emulated the "vibe" of a vintage EQ called a Pultec. I listened to it and had shivers up my spine: "That’s the Cat Stevens sound!" I said to myself. I could feel myself back in my college dorm listening to a Cat Stevens album. It was a perfect recall experience. The unique “vibe” of that saturation plugin re-created an experience I had stored up in my memory banks for years. So that was the very first plugin I bought. (Author’s note: A recent AI search I did suggests that Cat Stevens’ recordings, given the time-frame and studios in which they were made “probably did” use a Pultec EQ but that there are no resources available that conclusively established that he did. My ears sure think he did.)

Well, I’ve bought quite a few plugins since then, and a significant percentage of them have been emulation plugins. But as the emulation plugins-- and the credit card bills-- accumulated, I began to realize that while different audio engineers online boasted of how, say, a particular compressor emulation plugin captured the sound of their favorite band, that's all the plugin did. It allowed that person to relive his or her own personal memory. No one else’s. In fact, two people in the same room listening to a piece of music some time ago likely will have very different memories of that experience.

Let me give an analogy. Suppose a friend of yours says taking videos of your child's upcoming birthday party is a great idea because when you watch the videos later you will get to relive that feeling you got when your child had the party. So your friend wants to sell you his video camera and promises when you watch your kid's party after filming it you will get this great feeling of nostalgia just like he does when he watches his son's birthday parties from past years. Meanwhile you see advertised a lot of new video cameras on the market that have further developed the brightness, resolution and image-taking capabilities of video for the same price. So you tell your friend thanks for the tip but you're going to get one of the newer cameras. He argues with you that you must use a camera that catches the images the way they used to be caught using the older technology to get that good feeling. Of course his logic is wrong: You are not trying to create his memories, you are trying to create your own memories and do it with better equipment!

Like that, while emulation compressors give a vibe of the 1960s or 1970s, new plugins have now been created dedicated exclusively to creating high tech saturation experiences. These “saturation plugins” give the audio engineer an incredible ability to adjust the components of saturation to finely-detailed specifications: Does this mix need higher order saturation? Odd or even order saturation? Should I apply the saturation in the upper mid frequencies or the whole frequency range? I can control all these variables. The issue is not what sounded great for a song recorded decades ago, it's what will sound great for the demands of the song we are mixing today.

So that is my story about saturation. In the last few years, my purchases have included the best pure tech saturators out there: Fab Filter’s Saturn, Izotope’s saturator modules in their Ozone, Nectar, and Neutron plugins (and their new Plasma), Softube’s Harmonics Processor, and Brainworx’s Saturator V2 among them. As I became familiar with them, I settled upon which plugin at which settings seem to work best for the particular song or spoken voice I am post producing. That’s what makes the job challenging, and that’s what makes it fun.

And there you have it. Many will say that post production of audio is all about getting the "tone" of the music, that is, capturing the true nature of the sounds of the instruments including the human voice. Quite true, but I would add two more things: Compression adds the “glue”, and saturation adds the “vibe". If the post production process can provide proper tone, glue, and vibe to to the recording, the audio engineer has contributed to the artistic completeness that the work deserves.